Accommodating Resistance: Why Train with Resistance Bands

As a physical therapist and strength & conditioning coach, I am always looking to get the most out of each exercise I can for my patients and clients. To do that, I’m often being very critical of each choice – what movement I chose, how many reps I pick, what kind of loading they should utilize, etc. In that process, I often find myself choosing to include some kind of accommodating

resistance for the individual to get more out of the exercise.

In this blog, I’m going to break down what accommodating resistance is, why it’s a really beneficial option of loading, review different ways that you can use accommodating resistance and set it up, and when you should use it in training. As you make your way through this article, I’ll provide various examples of each point to ensure you have a plethora of options to implement in your own training and level things up. So, let’s get into it!

What is accommodating resistance?

Alright, nerd talk time (I’ll keep this short). Accommodating resistance is a form of variable resistance, meaning that the amount of resistance to movement changes through the exercise. When you think of classic exercises like the bodyweight squat, as you go up and down, the amount of resistance (bodyweight) doesn’t change. If you were to add weight with something like a dumbbell in a goblet grip, the weight would continue to remain constant. In contrast, if you were to use something like band loading where you stand on the band and place the band over your shoulders, the amount of resistance would change through the motion.

There are a range of kinds of variable resistance, with accommodating resistance specifically, it means that the amount of resistance actually increases throughout the range of motion. When we go back to the squat with a band example, at the top of the movement the band is stretched out and “pulling” you down. As you descend down, the amount of stretch on the band decreases, and the degree of resistance goes down. Then as you rise back up, the band begins to get stretched again and the degree of resistance increases as you stand up.

This fundamental concept of accommodating resistance is critical to understand as you begin to apply it in practice with your exercise selection, range of motion utilization, and goal outcome from loading.

Why use accommodating resistance?

I’m a huge fan of accommodating resistance as I think that it can help individuals get more strength, increase their power production, train with less pain and discomfort, and become more athletic. In getting these gains, it’s important to ensure that you implement it appropriately so that you get the most out of your training.

When looking to utilize accommodating resistance with a movement, one of the first concepts to think about is the strength curve and resistance curve for the exercise. The strength curve of an exercise describes where an exercise is easiest versus hardest. For instance, when you compare a push up to a pull up, these movements have opposite strength curves. If you watch most people do push ups, they’ll cut the bottom range short, which is where the movement is hardest, and primarily do the top range, which is where it’s easiest. The push up has what’s called an ascending strength curve, which essentially means that as you near the top end of motion, the exercise gets easier. In contrast, if you ask most people what the hardest part of a pull up is, they’ll answer that the top is the biggest challenge. The pull up has a descending strength curve, which is the opposite of the push up, meaning that the bottom is the easiest and the top is the hardest. If you consider that, you can start to quickly see that during certain movements, accommodating resistance becomes a more ideal option for one than the other. In general, when you have an ascending strength curve movement – like a push up, bench press,

squat, lunge, tricep pressdown, etc – accommodating resistance often works really well with it.

Theoretically, when you perform these ascending strength curve movements with the addition of accommodating resistance, you could get greater increases in strength and hypertrophy with them. The maximal amount of resistance that an individual can use in these movements is generally limited by how much the individual can handle in the bottom position. For instance, when you do a bench press with full range, if you’re going to fail, it’ll be near the chest position. Through adding on band resistance, you would be able to continue using a similar amount of straight weight resistance that is challenging for the bottom position, but have the bands increase the degree of demand and effort after this range, generating more total resistance in the movement. By doing this, you would be able to accumulate more total tension for your working muscles and a higher amount of volume.

Andersen et al. 2016 examined this, comparing the amount of neuromuscular activity from the quadriceps and hamstrings during a squat done with three loading options – straight weight (barbell and plates), light accommodating resistance (similar to the pull-up bands) (2 bands), or heavy accommodating resistance (4 bands). To ensure that the total resistance across the conditions was as equal as possible, the researchers attempted to factor in the amount of band resistance experienced and reduced the straight weight added by the number of bands used. They found that with the accommodating resistance, there were greater degrees of quadriceps EMG during the ascent, with there being EMG amplitude with the 4 band than the 2 bands.

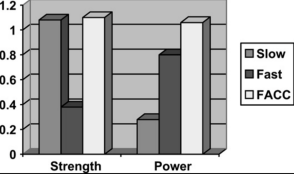

Rhea et al. 2009 conducted a similar study, this time having forty-eight NCAA Division 1 athletes train for 12 weeks, either using heavy straight weight resistance, lighter straight weight resistance, or lighter straight weight with the addition of bands for accommodating resistance. Other than the difference in the resistance, the athletes all followed the same program. After the 12 weeks, the researchers found that the athletes using the accommodating resistance had increased their strength as much as the athletes using the heavy resistance, but were also able to make more gains in power.

Image – Rhea M. Journal of Strength and Condition Research Volume. 2009;23(9):2645-2650.

These results in improvements in strength & power are further supported by research such as Joy et al. 2016 who saw better gains in rate of power development with baseball players, and for Riviere et al. 2017 that found larger increases in both velocity and power for rugby players using accommodating resistance over traditional free weights.

This increase in power development, along with the strength gains, is an incredibly important consideration for the usage of accommodating resistance. Baker & Newton 2009 examined the effect of adding accommodating resistance to the bench press to try and understand how the change in resistance results in these power production benefits. The researchers theorized that as the peak velocity during the lowering portion of bench press with accommodating resistance tends to be faster, it likely leads to a more rapid stretch shortening cycle that then leads to a post activation potentiation during the concentric, letting you be more powerful.

As you can see so far, there are some great benefits from the use of accommodating resistance, but there are some other ones that are often not considered. Earlier it was discussed that accommodating resistance works well with these ascending strength curve movements where the load increases where the exercise is easiest, which is conceptually the key benefit we have focused on so far. On the flip side, accommodating resistance unloads the movement in the position where individuals are weakest and tend to also have the most issues. For example, during the squat, there aren’t many people who struggle with aches or pains at the top of the lift, whereas if someone has an issue with squatting, it is usually at the bottom range. This same problem presents with the bench press, strict press, and even deadlifts.

This is something that I utilize very frequently in my practice as a physical therapist. I will commonly get individuals who present with a specific range of motion that is problematic, where the person is fearful of loading that range and has insufficient capacity for it. To overcome this, we are able to implement accommodating resistance that allows the person to train the ranges that he/she is more confident and comfortable pushing hard with a good level of resistance, but then deload the ranges where the person is hesitant or gets distinct symptoms. For instance, in my patients struggling with back pain they’ll be fearful of forward bending, particularly with resistance, that may limit them from picking up groceries, their children, or lifting heavier weights. By performing an exercise like a jefferson curl with a band resistance anchored down low, the person is able to gradually bend forward into deeper ranges, but the band unloads and the person is able to explore that range, then as he/she returns back up, can begin to get challenged to develop more strength. This happy medium of loading is often very successful in overcoming situations where people have stalled in their progress.

This concept of altering the loading during different phases of the movement instead of just reducing the overall load is one that can be applied in more athletic ways as well. For instance, when an athlete is working on increasing their vertical jump, increasing the eccentric loading the athlete must overcome and transfer into a vertical impulse is beneficial. This can be done through having the athlete hold onto dumbbells while going through different kinds of jumps like a standing squat jump or pogo leaps, however these methods of loading can be a disadvantage for the person by having them go slower on the ground during the acceleration phase due to the increased external load. In contrast, using bands can be a perfect solution to this by allowing the person to have no resistance during the jump, but then as the bands get stretched while the person goes up, the bands will then pull the person down at a faster rate, increasing the eccentric loading. I like to set up people with a resistance cord anchored on each side to a squat rack and then the individual can have a handle on each side, which is much easier to grip than trying to hold onto a thicker band.

From another perspective, some individuals are unable to tolerate the impact from jumping and avoid doing power training due to this. During a jump, the highest amount of challenge is not the actual jumping portion itself, but the ability to absorb the loading when you return back the ground. Research shows that this loading can get quite high, such as the knees experiencing between 2.4 and 9 times bodyweight during landing. These forces aren’t necessarily bad, but they can be more than many are able to tolerate, particularly when first getting into jumping. Implementing accommodating resistance can be a great option for deloading the landing, allowing people to practice jumping, begin working on the mechanics, and introduce the landing – but with less overall load. This can be done a few ways, two of my favorites are the broad jump with band resistance, where you set up with the band anchored and pulling backwards as you jump forwards, and the standing jump with band lower assistance, where the person grabs a band anchored above them and holds on lightly while jumping, but then pulls down on it after reaching their top height.

Summary

Accommodating resistance is a type of loading where the degree of resistance changes through the movement. The unique nature of the resistance changing through the exercise can be very beneficial when looking at building muscle or increasing strength as you are able to increase the total tension in a movement and have a higher demand on working muscles. This is generally best implemented with ascending strength curve movements like squats, bench press, push ups, and deadlifts.

The benefits of accommodating resistance are not just limited to strength focused movements though. This style of loading pairs very well with developing power and can be put into effect either with classic gym exercises, or it can be used with various jumping movements to have a higher eccentric demand.

Accommodating resistance also provides a unique benefit of allowing individuals to train movements and ranges that would otherwise be off the table. Through altering the loading profile, people can do movements that would be bothersome and train through ranges that would be ignored.

Author Bio:

Dr. Sam Spinelli is a doctor of physical therapy & strength and conditioning coach who specializes in helping individuals overcome injuries and set backs, reaching their highest levels of performance possible. He is the co-founder of Citizen Athletics & E3Rehab, two companies which focus on putting out evidence based content for fitness & rehab.